The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) went into effect on May 25th, 2018 and stipulates that companies processing personally identifiable information (PII) must carry out requests from end users to be ‘forgotten’ from their systems. Implementing this right to be forgotten (RTBF) for our products means that not only do we need to take care of deleting historical data, but also filter out new data uploaded by the Localytics SDK to our backend services. It is impossible to guarantee that data from opted-out users won’t end up in our ingestion pipeline due to the inherently unpredictable nature of distributed systems, so we have to do a GDPR status check against every data-point. To put this in perspective, we ingest on the order of 50k data-points per second on a typical day.

As an AWS-native shop, DynamoDB is our NoSQL database of choice for ultra low-latency high-throughput point lookups in our ingestion pipeline. We already use DynamoDB to track and update user profiles for every data-point. At current prices (2018) the required additional read capacity would cost an extra $4500 per month at our present volume.

In order to help reduce the extra costs associated with GDPR compliance, we took a look at bloom filters. Bloom filters are probabilistic data structures that allow for quick lookups and efficient memory usage. The tradeoff is that bloom filters have a non-zero false positive rate. However, it will always give you a positive answer for something that is actually in the bloom filter. The size and lookup speed of the bloom filter is directly related to this false positive rate.

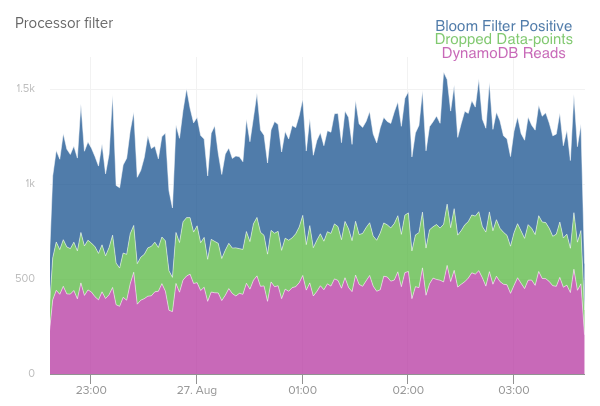

Our implementation of the GDPR data-point filter is as follows: We fill a bloom filter with opted-out users, serialize it, and upload it to S3. The bloom filters need to be recreated each time because you can only add, not remove keys. Our ingestion pipeline periodically downloads the newest bloom filter version and loads it into memory. We first check an incoming data-point against the bloom filter, and for every positive bloom filter check we make a call to a DynamoDB table that stores the user’s true opt-in/out status. When we verify that the data is from an opted-out user, we simply drop the data-point. This implementation allows us to adjust the amount of DynamoDB calls and thus our costs based on the false positive rate. Once we perform the check for that user against our DynamoDB database, we additionally cache the result to save on subsequent DynamoDB requests.

Let’s look at a typical second long window of our data ingestion pipeline and crunch some numbers. First, let me define 1 data-point/second as 1 dpps for convenience, also let’s assume that the dpps from opted-out users is small relative to everyone else. With 50k dpps being pretty standard for daily peak usage and a bloom filter false positive rate of 1 in 10,000, you’re looking at about 50 dpps making it through the bloom filter. Our caching layer (to handle duplicates) typically cuts the actual number of requests to the database in half, so in the end we actually only need to make about 25 dpps dynamo calls. This is only about 0.05% of all the data-points that we actually need to hit the database for and only amounts to about $2 of extra dynamo charges per month. The size of the serialized bloom filter files amount to about 750 KB each, so there is room to decrease the false positive rate even further as long as available memory is not an issue.

All in all, the pattern described above for doing simple filtering checks against a database turned out to be very successful. If we had only used a caching layer instead, we would be looking at about 1 thousand times more database calls. We are considering other places in our system where a dynamically updated bloom filter could be helpful in reducing database read costs. As long as you have sufficient memory available and are able to periodically and asynchronously recreate the bloom filter, it is definitely worth considering these handy data structures.